Lenin once said that: “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen”. On 24 February last, the commencement of the Russian invasion of the parts of Ukraine it didn’t already illegally occupy fundamentally transformed the Western security picture. The previous ‘Wandel durch Handel’ (change through trade) approach of dealing with authoritarian regimes, associated with the likes of Angela Merkel, had been seen as bestowing a ‘Friedensdividende‘ (peace dividend) to Western governments. Structurally lower defence spending was the reward for a perceived threat reduction.

As a result, many Western countries went into 2022 with antiquated platforms. By way of illustration, as of July five EU member states were still operating Soviet era fighter jets – Bulgaria (Mig-29, Su-25); Croatia (Mig-21); Poland (Mig-29, Su-22); Romania (Mig-21); and Slovakia (Mig-29). While Ukraine had made strides in modernising aspects of its military, most notably in terms of tactics, the backbone of its equipment was still based on Soviet platforms come the start of the 2022 invasion. Western countries, particularly those in Eastern Europe, rushed stockpiles of Soviet era equipment to help Ukraine defend itself against the aggressor.

The effectiveness of this effort is clear. As of 12 November, the Ukrainian Armed Forces had liberated around 75,000 sq km of the territory seized by Russia after 24 February, or c.63% of the total. The attrition of Russian equipment by the defenders has been astonishing. While the fog of war makes it difficult to quantify the exact damage inflicted on the invader, that fact that Russia has rushed 1970s missiles (Kh-55s); 1960s era tanks (T-62); 1950s era armoured cars (MT-LBs); and 1940s era anti-aircraft guns (S-60s) suggests that its quartermasters are digging around the back of the warehouses to sustain operations.

Ukraine has also, plainly, incurred severe losses. But deliveries of Soviet era kit from Western countries have been augmented by more modern systems, particularly ‘shoot and scoot’ systems like HIMARS which allow Ukraine to deplete Russian positions from afar. But, as the war has dragged on, inventory shortages have begun to impact.

One particular choke point for both sides is artillery. The Financial Times reported on 14 December that: “Russian forces have fired 10mn artillery rounds from its stock of 17mn shells at the start of the year”. On 2 December the same paper said: “During intense fighting in the eastern Donbas region this summer, Russia used more ammunition in two days than the British military has in stock. Under Ukrainian rates of artillery consumption, British stockpiles might last a week and the UK’s European allies are in no better position”.

While the resolution of the Ukraine war has yet to become clear, I see three lasting consequences for defence contractors.

Firstly, Western countries will structurally increase their defence spending, reversing some of the Friedensdividende. NATO countries’ GDP runs to more than $40trn, so every 25bps increase in spend as a % of GDP implies an extra $100bn+ annual outlay (and NATO’s guideline is for more than 20% of spend to go on equipment; in practice most members spend a far higher share on kit).

Secondly, there will need to be an element of catch-up spend to replenish inventories that have been run down to support the Ukrainian war effort.

Thirdly, the global export market is likely to be dominated by Western firms for many years to come, as: (i) Russia will presumably divert its own production to rebuild its shattered military; and (ii) The woeful performance of Russian systems in combat against comparable Western equipment will not have escaped the attention of officials tasked with procurement in third countries.

These three factors lead me to be very bullish on Western defence firms generally.

Within the Western sphere I’m particularly interested in European suppliers. The reason for this is that Europe has more ‘catching up’ to do on spend than the US. A June 2022 NATO communique estimated that this year’s defence spend across the bloc would be $1.1trn in 2015 dollars, split $723bn for the US and $328bn for Europe and Canada.

One leading European player is Rheinmetall. It has a rich heritage, having been founded in 1889, and a proven track record of innovation in products and services. It has two core verticals, security and automotive, although the indications are that the latter will be a less important part of the Group going forward. Rheinmetall employs 25,000 people and has 133 locations and production sites worldwide.

What I like about its security offering is that it has a huge range of products that can meet many requirements of the Western rearmament programme – armoured cars; tanks; transport vehicles; self-propelled howitzers; special forces vehicles; recovery vehicles; engineering vehicles; drones; ammunition; turret systems; air defence systems; sensors; observation and fire control units; laser systems; and a variety of support services (simulation and training; fleet management). In automotive RHM’s offerings span pistons, pumps, castings and valves.

OK, that’s the theory, but what is RHM’s track record like?

In 2011 RHM reported sales of €4.5bn; EBITDA of €538m; Operating Cash Flow of €290m; ROCE of 14.9%; EPS of €5.55 and DPS of €1.80. That year it had FD shares out of 38.33m. The order backlog at year end was €4.95bn.

In 2021 RHM sales were €5.7bn (a CAGR of 2% since 2011); EBITDA was €859m (a CAGR of 5% in the same period); ROCE was a strong 19.0%; EPS was €6.72 (CAGR of 2% since 2011); DPS was €3.30 (CAGR of 6%); and Operating Cash Flow was €690m (CAGR of 9%). FD shares out at end-2021 of 43.28m meant that the share count has grown at a CAGR of just 1% since 2011. Perhaps most significantly, the order backlog at end-2021 of €13.93bn has grown at a CAGR of 11% since 2011.

The huge order backlog provides considerable income visibility into the medium term and, for the reasons set out above, there is every reason to believe that this will remain the case for years to come. Indeed, RHM’s Q3 2022 results, released in November, saw management reaffirm guidance for 2022 of organic sales growth of c.15%.

Rheinmetall’s share price started 2022 at €83.06, but soared to €227.90 in the wake of the Ukraine war, reflecting the changed reality for Western defence spend. They subsequently slipped back a little, and I added it to my portfolio at €152.35 (inclusive of charges) on 17 October. The stock has since increased to €201.40 as of the close on 16 December.

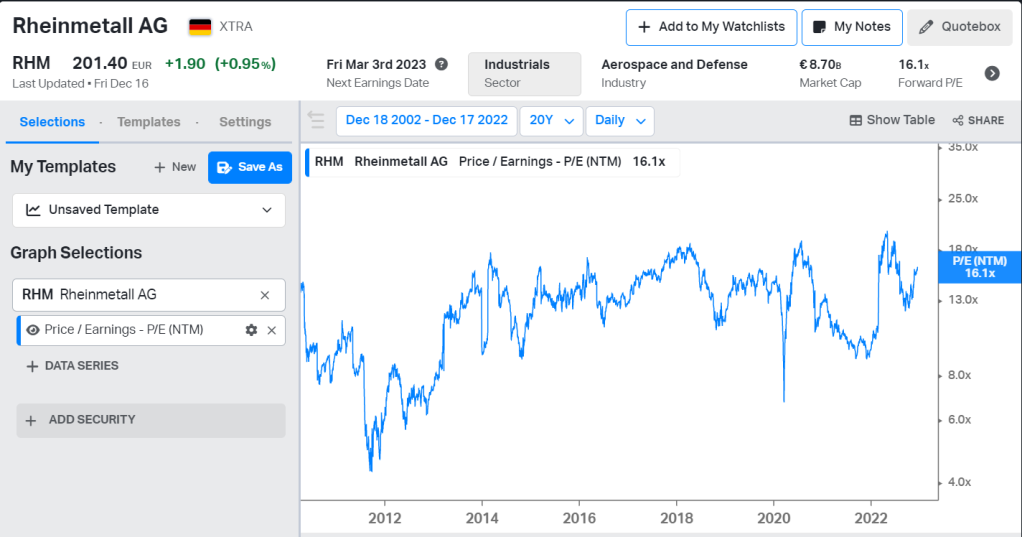

Despite this strong share price performance, the shares trade on an undemanding earnings multiple of 16.1x on a next 12 months basis, per Koyfin data. Yes, this is towards the high end of the range it has traded at over the past 20 years, but I would highlight that, for most of that period, Friedensdividende would have been the prevailing thought that would come to mind if considering the outlook for Rheinmetall and its European peers.

Sell-side consensus sees earnings growing from 2021’s €6.72 to €19.645 in 2025 – an astonishing CAGR of 31% (which compares to the CAGR of 2% in the 10 years to 2021!). A 16.1x forward earnings multiple looks extremely undemanding when set against that forecast growth profile.

Is this growth profile realistic? On 16 November Rheinmetall held a Capital Markets Day (CMD) titled: “Supercycle 2.0”. Management outlined its expectation for “accelerated growth in all end markets”, supported by rising NATO spend generally and the addition of new members Finland and Sweden. In RHM’s home market, the German government has committed to spending €100bn on new military equipment while raising annual defence spend by €50bn. In automotive, RHM sees opportunities in electrification and emissions reduction.

RHM is also focused on portfolio management, exiting non-core businesses and expanding in structural growth areas (including in automation, digitisation and electrification). A good example of this portfolio management is the proposed €1.2bn acquisition of shell producer Expal in Spain. For Germany alone to reach its target inventory of shells that would consume 10 years of [inadequate] existing industry capacity. Given that capacity upscale is slow and expensive, the “smartest move is to load available idle capacities”. Expal more than doubles RHM’s capacity in rounds, while Expal is currently only operating at around 50% of capacity.

Returning to the forecast near-trebling in earnings between 2021 and 2025, it is worth noting that the RHM CMD assumes revenue growth from €5.7bn to €10-11bn over that timeframe, with EBIT margins widening from 10.5% to c.13.0% in the period. That guidance, presumably informed by the order backlog I mentioned above, gives me confidence in sell-side earnings forecasts. Another factor that gives me confidence is the guided step-up in capex to support this growth – having invested €277m in 2020 and €242 in 2021, RHM is guiding investment of €400m, €600m, €450m and €450m in 2022/23/24/25. Capex of well below 1x annual EBITDA seems eminently realistic to me.

Apart from (presumably) share price growth, shareholders will share in the higher earnings, with the Group guiding a payout ratio of 35-40% in the mid-term and flagging the possibility of buybacks (the latter is “currently not a priority”).

For me, I see RHM as an inexpensive play on the structural growth story in Western defence markets. As an aside, while I appreciate that ESG considerations will be a turn-off for many investors, the lesson from the Russian army’s cruelty in Ukraine is that security investment is a must-have.

If you wish to be notified of updates to this blog, then why not consider subscribing using the form below?